REPORTS ALL YOU NEED

TO KNOW CASE STUDIES

& LESSONS REALISING

THE BENEFITS GLOSSARY LINKS CONTACT

Introduction

Trees bring a host of benefits to the East of England but, before exploring these in detail it is helpful to understand the different respects in which trees contribute to ourselves throughout the region, as well as the nature of the woodlands concerned.

|

Based on Ordnance Survey mapping with the permission of |

i. Total wooded areas

There are about 144,000 hectares of woodland in the East of England, or 7.6% of the total land area. In addition, there are approximately 13.5 million trees outside woodland in the countryside, 14,000 kilometres of hedgerows with a high proportion of trees and an immense but un-quantified urban tree stock. All told, trees and woodlands are a vital part of the character of the East of England, both rural and urban. The area of woodland has increased steadily and significantly over the last 100 years, with the most obvious examples being the mainly coniferous woodlands established from the middle of the 20th century. Since 1980 there has been over a 25% increase in area, over half of this has been through planting small woodland blocks of predominantly broadleaved species.

![]()

Figure 1: The distribution of woodland of 2 hectares or greater in the East of England

Trees...make a major contribution this region's landscape

Whilst the extensive coniferous plantations of Thetford Forest are the largest blocks, 38% of the total woodland area consists of woodland less than ten hectares in size with 19% being less than two hectares.

There are a large number of designated and undesignated parklands, areas of wood-pasture and historic landscapes, in which trees and woodlands play a major part, many are of international importance. English Heritage maintains a register of parks and gardens. http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/caring/listing/registered-parks-and-gardens/

ii. Trees - a pattern of diversity

The East of England woodlands encompass a rich diversity, for example:

- Cambridgeshire’s woodlands are oak-ash on the clay soils and ash-hazel-field maple on the chalkier soils, both of which are associated with distinctive ground flora

- Norfolk has important wet woodlands and increasingly rare woodland species such as the spotted flycatcher.

- Norfolk and Suffolk have a heritage of wood-pasture and parkland, Staverton Thicks being the prime example

- Essex is noted for its ancient hunting forests of Epping, Hatfield and Hainault, as well as native black poplar

- Bedfordshire has a series of ancient woodlands along the Greensand Ridge and

- Hertfordshire includes part of the Chilterns beech woods and is important for many species that depend on a long continuity of woodland cover, particularly plants, fungi and invertebrates.

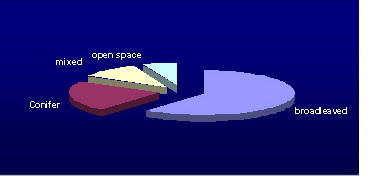

The East of England has a diverse woodland resource with broadleaved woodland the dominant forest type representing 61% of all woodland. Conifer woodland represents 22%, mixed woodland 11% and open space within woodlands and felled areas 6%. Corsican pine is the main conifer species and Oak the main broadleaf species.

The East of England has a diverse woodland resource with broadleaved woodland the dominant forest type representing 61% of all woodland. Conifer woodland represents 22%, mixed woodland 11% and open space within woodlands and felled areas 6%. Corsican pine is the main conifer species and Oak the main broadleaf species.

Figure 2: Breakdown of types of woodland in the East of England

iii. Trees and the environment

The percentage of this that has been designated as Ancient Semi-natural Woodland (i.e. it has existed relatively unchanged in species composition since at least 1600) is higher than the national average. As well as being a very important nature conservation resource, ancient woodland is the repository of significant quantities of archaeological artefacts and ancient woodland often preserves evidence of pre wooded landscape and historic woodland management practices.

Trees...with conservation significance

Woodlands of nature conservation significance are not limited to those that are ancient semi-natural. For example, the coniferous areas of Thetford and on the Suffolk coast, where Corsican and Scots pine predominate, are of international importance having been designated as Special Protection Areas for woodlark and nightjar.

Wood forms a valuable habitat for a number of key species and, although the total area of woodland in the region has continued to increase, there are situations where woodlands may be lost to create other habitats and there are other threats such as deer.

Habitat restoration to non-woodland habitats

The removal of recent plantations from important semi-natural habitats (particularly

lowland heath and wet woodland to create reed beds) has increased in recent years. This removal is in response to the UK Biodiversity Action Plan and it is likely that there will be continued pressure in the future. The recently published Open Habitats Policy of the Forestry Commission sets out a process for establishing open habitats such as that of heathland in the Brecks. The policy can be found here; http://www.forestry.gov.uk/england-openhabitats

iv. Trees and society

Trees...a recreational resource

The woodlands of the region provide a very important recreational resource, with an estimated 21.2 million leisure visits per year (ELV survey 2005).Of the total woodland area of the East of England, about 70% is privately owned, 18% managed by the Forestry Commission with the remainder owned by charities and local authorities.

Trees...create urban character

Trees associated with public green space, streets and private gardens are a vital part of the character of all the towns and cities and affect many more people on a daily basis than do rural woodlands. In many cases, potentially very harsh townscapes have been dramatically softened by the presence of trees; they also provide much needed shade in summer and help improve air quality.

Of the national Community Forests three - Marston Vale, Thames Chase and Watling Chase have been established in the East of England, which have encouraged the creation of multi-benefit woodland in areas that had suffered considerable landscape degradation close to urban centres. There are also many other important local initiatives, such as the Norfolk County Council community woodland scheme.

History and Heritage

Trees and woodlands are an integral part of the landscape and history of the East of England. Many of the woodlands have existed for hundreds of years, and as such they help define historic landscapes. In parts of the East of England, the rural landscape pattern has remained relatively unchanged since mediaeval times. The East of England also has many internationally important parks and gardens designed by some of the greatest landscape designers – Holkham and Wimpole estates being good examples.

Individual trees can be very long lived, in some cases extending to many centuries. They can be cultural features in their own right, for example Kett’s oak in Norfolk. Norfolk County Council has developed a database of over 5000 such trees which can be found on their biodiversity information service website.

As well as being part of the heritage, woodlands are frequently the repositories of some of its best-preserved archaeological features. They may contain features relating to woodland management, including wood banks and saw pits, and many other land-use artefacts. The general lack of cultivation within woodlands has meant that a variety of archaeological remains are to be found in relatively undisturbed condition. Examples include Bronze Age burial sites and villages, Roman field systems and mediaeval houses. The apparently ancient woodlands to the south of Grafham Water contain perfectly preserved ridge and furrow – evidence of mediaeval agriculture.

In many cases, the presence of such sites is unknown as few woods have been subject to systematic survey and recording. The archaeological features surviving in woodlands have great educational and recreational potential. Thetford Forest masks the remains of an internationally important warrening industry that thrived for centuries on poor Breckland soils before the forest was planted. http://www.brecsoc.org.uk/rabbit_warreners.htm

v. Trees and the economy

The woodlands of the East of England have long provided materials for construction purposes and there are many very fine examples of wooden church roofs and timber framed houses, a prime case being the village of Lavenham in Suffolk. These illustrate the extreme durability of wood as a construction material, with many being over 500 years old.

Sustainable woodland management practices respect the cultural heritage of the East of England encouraging the creation of new woodland that is in keeping with local landscape character and avoiding damage to any subterranean archaeological sites and earthworks. The Forestry Commission publishes a series of guidelines on this and other subjects.

Woodland has a role in providing valuable opportunities that benefit human health and wellbeing, economic sustainability, maintenance of environmental assets and addressing the imperatives driven by climate change. The estimated value of woodland in the East of England is put at £1.3 billion; this is a midpoint value estimate and represents the level of wealth generated by forest and woodland each year.

Market benefits £ millions |

|

| Field sports and game | 81.0 |

| Timber and wood products | 345.5 |

| Recreation and tourism | 550 |

| Housing and industry | 30.6 |

Other benefits |

|

| Air quality and water management | 33.5 |

| Biodiversity | 71 |

| Carbon sequestration (annual figure) | 41 |

| Health costs avoided | (19.5) |

| Education costs avoided | (1.23) |

| Landscape | 124 |

| TOTAL WEALTH | £1,297.3 or 1.3 billion |

| Carbon asset stocks | 3,306 |

| Table 1. Summary of Woodland Wealth as at 2010 ['Click' here to return to previous page] |

|

For more detail about the economic value of trees use the menu to the left to access the 'Economic' data silo.

vi. Trees contribution to ecosystem services

In 2000 the United Nations developed the Millennium Ecosystems Services approach , which brought together the variety of ways in which nature delivers benefits and support to humans called ecosystem services or ‘natural benefits’. This approach could be used by decision-makers, planners and policy-makers to help them take account of those services when making development decisions, so as to ensure continuity or increase in services.

Trees...a fundamental feature of ecosystem services

This approach recognises the way in which the physical and biological components of the environment work together as a single functioning ecological system i.e. an ‘ecosystem’. An ecosystem will include the plants and animals that make up a habitat as well as the other elements which enable the habitat to function; including soils, water, climate, human management etc. A whole planet, a forest or a single tree can be an ecosystem.

Ecosystems provide a range of benefits some of these are essential for life e.g. if taken on a planetary scale the regulation of the climate (see diagram below).

| Examples of ecosystem services provided by woodland | |||||||||||

| Provisioning services | Regulating services | Cultural services | |||||||||

| Wood fuel Fibre Timber Biodiversity – Genetic resources BiochemicalsFruits, nuts, meat ,fungi |

Climate regulation – carbon sequestration and moderating local climate Water regulation – flood attenuation Water purification – filtration of water. Pollution absorption Shelter |

Recreation and tourism Aesthetics – landscape Education – forest schools Health benefits – mental and physical Cultural Heritage – The historic environment Sense of place – ‘our wood’ Spiritual and religious Inspirational, Employment |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| Figure 3 | Supporting services |  |

|||||||||

| Vital for all other ecosystems services Nutrient cycling Water cycling Soil formation. |

|||||||||||

vii. Trees amenity values

a. The need to estimate the value of a tree

Increasingly tree owners are recognising the need to value their tree stock, in much the same way as local authorities value their infrastructure and building stock, or developers their assets. By attaching a general value to trees and woodlands they are then more likely to be included in development and properly looked after.

b. Various methodologies

There are four methods[iv] of achieving these outcomes:

CAVAT

A comparative study of valuation methods by the Tree and Design Action Group published in 2008 indicates that the most efficient way of dealing with large numbers of trees (i.e. not only veteran trees, but also stands of trees and woodlands) is the Capital Asset Value Amenity Trees method - or CAVAT for short.

- Developed in the nineties in the UK, the CAVAT system uses a hand-held scanner that can download direct to a database.

- A value for a tree is ascribed that has been predetermined by its size.

- The system then adjusts the tree's value according to a wide set of factors/benefits to provide a measure of the individual tree's value.

- CAVAT supplies a limited assessment of social/cultural values and, unlike any other system it factors in nature conservation and biodiversity.

- Usefully, there is also a quick method for assessing larger tree populations with less detail.

i-Tree

The second method, developed by the US Forestry Service, is called i-Tree.

- This computer-based system uses a module or sub-system called STRATUM that was specifically designed to assess large populations of street trees.

- Like CAVAT, i-Tree is also appropriate for valuing tree populations over wide areas.

- i-Tree offers a limited assessment of social/cultural value. Altogether it has the advantage of flexibility, detailed output and assessment of a wide range of benefits (although not as wide as CAVAT).

- While its output is automated it is not widely used in the UK, possibly because it requires more detailed input than CAVAT.

Helliwell

Despite being slower than the other methods, this manual system has been extensively used in the UK.

- Developed in the sixties in the UK, this method applies expert judgements, on a tree-by-tree basis, to estimate an individual tree's amenity value, expressed in pounds sterling.

- Helliwell does not consider environmental, social or cultural benefits.

- It seems best suited to single tree and small community evaluations or urban woodlands.

DRC

The second manual method is Depreciated Replacement Cost (DRC).

- Developed by the Council for Tree and Landscape Appraisers in the US, this approach is based on a recognised method of financial asset appraisal.

- To arrive at a final value for a given tree, this method uses a formula covering its various characteristics, condition and location.

- The formula's valuation is then corrected for depreciation.

c. Definitive values can be calculated

Whichever valuation method planners or developers select, a rigorous measure of a tree or woodland's value can then be calculated[v]. Once trees have been assigned recognised values, the need for retaining or planting new or replacement trees in developments becomes more evident.

That trees can increase in value as they mature acts as a further incentive for retention. Finally, it is also possible to use these methods to predict a tree's subsequent value at maturity and demonstrate how this might positively enhance a development's future resale value.

The methodology employed by the University of Gloucester to arrive at an evaluation of the wealth of woodlands was complex.

The report has explored the literature from 2002-2010 and updated the woodland values from 2003 based on new information, and in some cases alternative approaches to measuring benefits. The report addresses two major aspects. First, it describes and evaluates the importance of woodland wealth to the East of England in broad terms, emphasising the significance of public benefits which are often not reflected in market terms. Second, it assesses the economy of woodlands and forests, addressing both the timber production and processing industry, and the more local but very significant role played by woodlands in the economy.

viii. Threats to trees

a. Development

Development is one of the biggest threats to woodland and its biodiversity and, despite the current financial crisis and the slump in the housing market, there will continue to be a need to house the increasing population and maintain the economic buoyancy enjoyed by the East of England.

Development pressure, whether for housing, industry or transport infrastructure, can result in felling of trees and woodlands. The population of the East of England is projected to grow from 5.7 million to 6.3 million, growth of 10 per cent over the period 2008 to 2018, the highest percentage growth rate of all regions of England[ii]. Looking at ways development can incorporate woodland can lead to innovative developments and more sustainable communities.

The fact that trees and woodlands would need to form an integral part of these developments is accepted by Government: in the consultation draft – ‘An invitation to shape the Nature of the Environment’[iii] it states:

”England’s trees woods and forests, ranging from individual trees to networks of woodlands in the countryside, are a unique asset –rich in biodiversity, popular places for recreation and leisure, producers of products such as fuel and wood for use in our daily lives and an important part of our response to climate change. We need to manage and expand this resource sustainably – for our generation and for future generations recognising all of these multiple benefits”

In addition there is huge potential to use local wood for a range of construction related products. With the UK currently the world’s largest importer per capita of timber and second only to China in value, some £11 billion, there is enormous potential.

b. Excessive browsing

The very high deer population in the region continues to threaten the success of woodland regeneration and a number of SSSIs are in poor or unfavourable condition due to this. Although, in the majority of cases woodlands will continue to exist, their structure and composition are likely to be significantly altered. The Deer Initiative, a partnership of organisations involved in the management of land, is responding to this threat and recently the Wild Venison Project has been established in the East of England. A project with support from the Forestry Commission and European funding, it is an attempt to develop a wild venison supply chain to ensure a number of beneficial outcomes:

- reduce habitat loss and enable woodland regeneration by removing deer,

- cut road traffic accidents caused by deer and

- bring unmanaged woodland back into management.

c. Pests and disease.

Climate change and the expansion of international trade are likely to increase the threat posed to Britain's woodlands by tree pests.

In response the Forestry Commission, with private sector support, has set up a Biosecurity Programme that aims to:

"Preserve the health and vitality of our forests, trees and woodlands through strategies which exclude, detect, and respond to, existing and new pests and pathogens of trees, whether of native or exotic origin."

The Programme will be directed by the Biosecurity Programme Board and will include representatives from across the Forestry Commission, Forest Research and the forestry and wood using sectors.

As there is a possibility that disease and pests become a greater threat to trees, species choice and provenance of trees for planting new woodlands will become an important consideration. For example, while we may still be planting oak, but it may be we need to plant genetic stock from Southern Europe.

![]()

[i] www.maweb.org/en/index.aspx

[ii] www.rightsandwrongs.co.uk/asia/other/5599-reference-uk-population-growth-expected-highest-in-the-east-of-england

[iii] http://www.defra.gov.uk/environment/natural/whitepaper/

[iv] For a fuller assessment of the four valuation methods see 'Application and methodologies: a review', Vadims Sarajevs, Forest Research, 2010. Also note the 'Summary of Tree Valuation Based on CTLA Approach' - Council of Tree and Landscape Appraisers (CTLA), 2003.

[v] In Appendix 2 of CABE Space's 'Making the invisible visible: the real value of park assets', published in 2009 are examples of tree valuations conducted in two UK parks. At Highbury Fields in Islington, using the CAVAT system, its 578 trees were valued in 2008 at £44,960,886. While in the same year 6,756 mature trees were valued, using the Helliwell system, at Sefton Park in Liverpool at £86,645,700.